It is well documented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that diabetes, with projections to impact one in three adults by 2050, brings with it a multitude of related risks and side effects, the most serious—and life-threatening—of which are heart attack, stroke, cancer and kidney damage. Others include fatigue, digestive (bloating, heartburn, nausea) and damage to blood vessels and nerves. Vision difficulties, such as cataracts and glaucoma, are also well documented (CDC) and generally monitored.

|

|

|

While there is also overwhelming evidence linking diabetes to hearing loss, it seems to fly a bit under the radar.

“It is more common than you might think,” said educator and dietician Joanne Rinker, MS, RD, CDE, LDN.

Rinker estimates that the rate of hearing loss for the 34.2 million Americans with diabetes is twice as likely and 30% more likely for those with prediabetes (whose blood glucose is higher than normal but not high enough for a diabetes diagnosis).

She added that hearing loss in a person with diabetes often presents earlier than in those without diabetes, and the risk increases when that person has co-conditions (neuropathies, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease).

Rinker’s background is in nutrition, and her first position was working with people with diabetes. She learned quickly that there are significant rewards to helping a person learn about all components of the ADCES7 (self-care behaviors for diabetes) and improve outcomes. This list includes healthy coping, healthy eating, active living, taking medication, monitoring, reducing risks, and problem solving.

She said, “As it relates to this topic, screening and being treated for any hearing loss will reduce risks of further issues with hearing loss and the ability to process speech, interact socially, and beyond.”

|

|

|

Christopher Spankovich, AuD, PhD, MPH, is an audiologist and hearing scientist who says he became interested in the relationship between metabolic functional status and hearing during his work toward his PhD. In fact, his doctoral dissertation was on the effects of diabetes on cochlear and auditory neural function.

Spankovich has subsequently been involved in clinical and epidemiological studies of cardiometabolic function and the relationship to hearing and balance outcomes. He believes the challenge to establishing awareness is lack of formal recommendations for hearing and balance screening in adults.

“Diabetes does not commonly cause severe to profound hearing loss, but rather increases risk for acquired hearing loss and enhanced risk for balance dysfunction with onset of these problems earlier than observed in persons without diabetes,” he said, adding that hearing and balance screening allows us to establish a baseline to be able to observe changes earlier and provide appropriate recommendations for prevention and early intervention.

Spankovich says the patient care model for a person with diabetes is similar to that for any group with increased risk (e.g., occupational noise exposure):

- Educating providers (primary care, diabetes educators, nurse, etc.) about the relationship between diabetes and hearing-balance and importance for the patient’s function and quality of life.

- Routine hearing and balance screening starting with simple questions to referral for advanced diagnostics.

- Education on prevention, such as reducing exposure to loud sounds.

- Education on healthy living and diabetes control; this is important for hearing-balance and overall health status.

- Improved access to audiological management services, including but not limited to hearing aids, aural rehabilitation, auditory training, etc.

|

|

A DREAM GONE; REALITY FOUND

Kathy Dowd, AuD, is the executive director and founder of The Audiology Project. This is a far cry from when she graduated with a degree in French in 1972, hoping to teach and/or see the world as an airline hostess.

“The year before graduation, high schools started cancelling foreign language instruction, so this dream quickly disappeared,” she said. “I worked as a social worker and research assistant for the next few years and had free tuition to go back to graduate school.”

A research administrator mentioned audiology and urged Dowd to take a few courses. That led to graduation in 1978 and 41 years as an audiologist.

The more current work of advocating for audiology in diabetes care started in 2011 when a family member was diagnosed with diabetes late in life.

Recalled Dowd, “When her son, who supervises diabetes at the state level, had not heard of diabetes causing hearing loss, I asked who gave his agency diabetes information and funding. He responded that CDC was a main resource and supplied educational information for state programs. Reaching out to CDC, I discovered they did not know of this connection of diabetes to hearing loss.”

By 2016, the CDC was knowledgeable enough to suggest inclusion of hearing in its recommendations.

Dowd then created the nonprofit organization, The Audiology Project, and called a summit conference of the AAA, ASHA, and ADA, as well as AOA, CDC, diabetes educators and knowledgeable audiologists for hearing and balance issues.

The group convened at Salus University in September 2016 and, after a day of presentations and discussions, gave a green light to move this subject forward.

A publication in Seminars in Hearing in 2019 by audiology experts, and CDC’s continued working to vet audiology management and monitoring of hearing and balance in diabetes care, has created a space on CDC’s website about hearing and balance.

|

|

|

For Rinker, it all hits a lot closer to home.

“I am a person with diabetes myself, and I have significant hearing loss,” she said.

Figuring out why this is—in her case and with so many others—shows the same pattern as with other diabetes-related issues.

The damage that elevated blood glucose has on the other small vessels in the body is similar in the ear. When glucose levels are high, the small vessels in the inner ear start to break and the broken blood vessels disrupt normal hearing.

Over the last 10 years, Rinker and her colleagues in the field have learned enough about the connection and how important it is to assist people with diabetes and hearing loss to improve their quality of life while also decreasing risks associated with diabetes.

“We know that hearing loss is gradual, and while hearing is diminishing, so is the person’s ability to process speech,” she said. “Over time, not only does a person lose the ability to hear clearly, they are also losing the ability to process the words and sentences being said by their family, friends, and colleagues. This requires practice to relearn how to process speech. The good news is that our specialty is poised to screen and advocate for treatment of the populations we serve.”

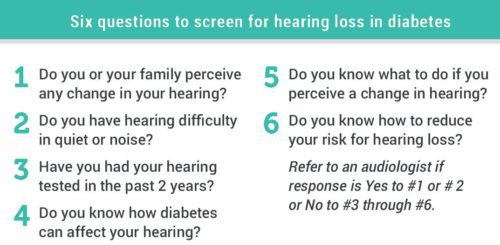

Rinker sees a large opening for diabetes care and education specialists (DCES) to make an impact on hearing health, adding that it is very important that DCES add this screening to their initial assessment and annual follow-up. For example, incorporate a screening questionnaire that addresses if the patient perceives changes in their own hearing, if family members notice changes, and if they’re even aware that diabetes can impact hearing. Based on the results, the DCES can choose to make a referral as needed.

“For this to be a successful process, the DCES must take the time to build a relationship with an audiologist,” Rinker explained.

|

|

|

While Diabetes I generally develops in childhood and commonly requires insulin, Diabetes II can develop in adulthood and, along with genetics, be the product of poor diet and exercise. The disease can be managed; with levels coming into the normal range with medication (and diet and exercise), one naturally wonders if any hearing damage can be restored.

Said Rinker, “If the damage was minimal, it can be reversed. If there has been extensive vessel or nerve damage, it may not be reversed, but it is possible that treatment options, including hearing devices, can allow for one to be able to hear all decibels again. I encourage [individuals] to see a DCES, get screened, and work closely with an audiologist to improve hearing and cognition.”

|

|

|

There is a pathophysiology of diabetes on hearing and balance. Diabetes causes disruption in small blood vessels throughout the body, says Dowd, as well as neural degeneration.

“For hearing, this disruption can cause not only peripheral hearing loss, but due to microangiopathy in the brain, also central auditory processing disorders,” said Dowd. “For balance, there appears to be more BPPV associated with diabetes, which can be easily treated if identified.”

Dowd explained that the eighth nerve transmits information from both the cochlea and vestibular system to the brain, so nerve degeneration will affect both systems.

“There is much still left to be discovered in research and NIDDK welcomes research applications from audiologists regarding diabetes,” said Dowd.

|

|

|

As important as convincing agencies (such as the CDC) to acknowledge the connection, challenges, and issues related to hearing and diabetes, developing strategies to build awareness of this connection is also critical.

Said Dowd, “Hearing loss is an invisible handicap. Because of anosognosia (the inability of a person to recognize a sensory disorder), many people with a hearing loss cannot determine they have a hearing problem.”

She added that physicians see anxiety, depression and confusion before suspecting hearing loss.

“CDC has recommended that audiology focus on educating primary physicians about hearing loss, risk of falls, CAPD, and diabetes and perhaps give them tools to screen for any hidden problem,” said Dowd, who added that The Audiology Project has many educational tools and presentations on its website, including the new CDC flyer, available for audiologists to download and use. You can customize the Healthy Ears flyer with your practice contact information: www.theaudiologyproject.com/education-materials.

She also suggested joining a TAP state cohort and organize outreach in your state, and sign up for newsletters and blogs. Dowd pointed to a large physician certification program that is looking to develop a sensory function assessment that will include vision, neuropathy and hearing screenings.

But those wheels move slow.

“This development process may take several years, but audiology doesn’t have to wait to educate doctors and nurse practitioners on how to effectively screen hearing and balance,” she said.

Dowd urged old-fashioned proactivity by picking up the phone and scheduling a visit to greet your local physicians or give a presentation to medical society meetings.

Spankovich, who is also involved in The Audiology Project, had endeavored to fill the void of a lack of formal guidelines. His recommendations with colleague Krishna Yerranguntla were published as recently as 2019, as well as another paper in 2020.

“Both manuscripts offer some easy-to-follow guidelines,” he said. “In brief, evaluation and management of the patient with diabetes and hearing loss/balance issues is not much different than any other patient, but there is greater risk and, therefore, appropriate and timely screening and referral are critical. Furthermore, we must look beyond the ear and consider the general health of the patient and implications for hearing and balance dysfunction.”

|

|

|